Page

1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page

4 | Page 5 | Back

to Work Page

The

COs worked hard in the camps and according to newspaper their work

was appreciated. Report 1

50

years after the CO's service, In 1988, on the fiftieth anniversary

of the Sayward fire, Hon. Dave Parker, the Minister of Forests for

British Columbia, gave the following speech:

Good

afternoon Ladies and Gentlemen:

We

are standing beside the first forest in British Columbia to have

been raised from the ashes almost entirely by the hand of man.

This new Sayward Forest was planted, nurtured, and is growing

to maturity as a result of human effort.

Looking

at these stands of healthy, vigorous trees today, it is difficult

to imagine the scene of total devastation left after fire consumed

more than 30,000 hectares (75,000 acres) of this forest fifty

years ago.

The

first had been a major contributor to the local economy for many

years before the fire. Logging had started in 1889 with ox teams

skidding logs out to Elk Bay. The ox teams eventually gave way

to railway logging which was in turn replaced by tuck logging

in 1954. The gentle landscape in the Sayward area, along with

stands of prime timber, favoured relatively easy logging but also

created ideal conditions for the rapid spread of forest fires.

Logging practices of the time, which allowed slash to be left

on the ground, provided abundant fuel. Chances of a fire starting

in dry weather were always high near logging operations because

of sparks from steam engines and other equipment.

So

it was on July 5, 1938 when sparks from a yarding engine operating

just north of Campbell River started a fire in some felled trees.

The fire spread rapidly and within a short time it was apparent

that a major conflagration was under way. One newspaper account

of the time described it as a series of small infernos where old

snags burnt like candles on the devil's birthday cake.

Up

to the time of the Sayward fire, reforestation in British Columbia

and everywhere else in North America was accomplished mainly through

natural regeneration. However, it was realized that without a

massive artificial reforestation program, the Sayward would never

again be a productive forest. The idea of planting seedlings over

an area almost as big as Quadra Island was overwhelming in 1938.

The

problem wasn't just planting trees. The snags

had to be removed first before the trees could be planted. If

not, the snags would remain a fire hazard and threaten the new forest.

David Jantzi talks about his job as a snag faller and why it was

important.

David Jantzi talks about his job as a snag faller and why it was

important.

|

|

|

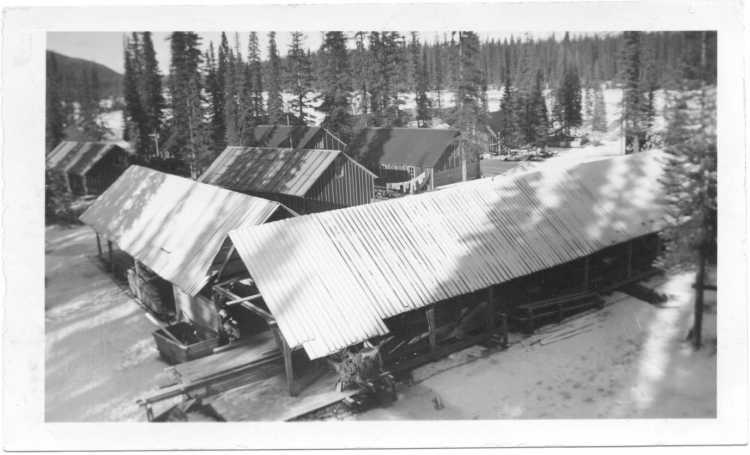

| A sawmill at a CO camp |

The saw mill at Camp 21, Radium, BC |

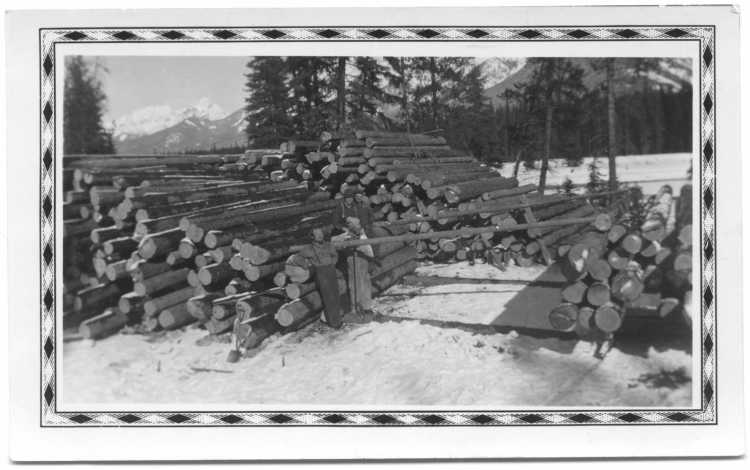

COs stacking logs near the sawmill |

Gordon

Dyck explains how the conscientious objectors removed the snags.

“Snagging

was a completely new experience for us prairie fellows. We always

worked in teams of two. Our tools were a six or seven crosscut

saw and a flask of diesel fuel to lubricate the saw if there was

a problem with pitch [sap]. Each of us had a falling axe which

was kept razor sharp.

First,

we always tried to determine which way the tree wanted to fall,

for if we were wrong, trouble was sure to follow. To force a tree

to go contrary to its inclinations was almost impossible with

our limited tools. It could have been done with a hammer and wedges,

but these were heavy and seldom carried. Sometimes we couldn't

tell which way a snag wanted to fall. To start with, every snag

had to have a substantial undercut to ensure safety in falling.

This was done with the axes, both men chopping alternately, so

it proceeded quite rapidly.

Once,

my partner Ike Neufeld and I were working on a snag that was about

three feet in diameter and about 10 feet [3 m] high where it had

broken off. It had no branches whatsoever. We proceeded to undercut

it on the correct side (we hoped), and then began to saw. After

sawing in a good distance we drove our axes into the cut to prevent

the tree from settling down on our saw – which it was sure to

do if we were wrong about its lean. After sawing to within an

inch of the undercut, we tried to force it to fall by prying with

our axes, but could not make it go. So we removed one handle from

the saw and drew it out so it wouldn't get broken if the tree

went backwards. Next we took our axes and cut the tree completely

off to let it go whichever way it preferred. But, strangely we

couldn't make it go backwards either. After trying for some time

to no avail, and wondering what to do next, the tree suddenly

started going backwards. I yelled a warning at Ike and he ran.

He had a very close call that day. Through some previous close

calls of my own, I had learned to keep looking up and taking a

few steps in the right direction. Sometimes when a tree fell into

another one, it could bend over and throw dry branches or tops

at us, so looking up was very important. [ASP, 61]

|

|

|

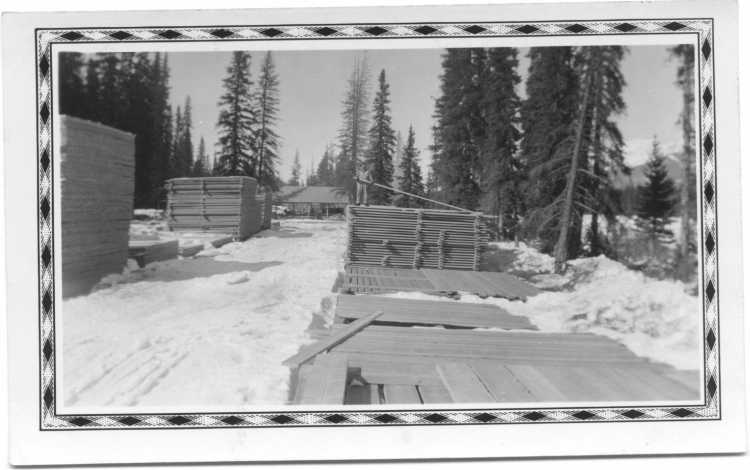

| Finished lumber from the sawmill |

"Topping" a tree |

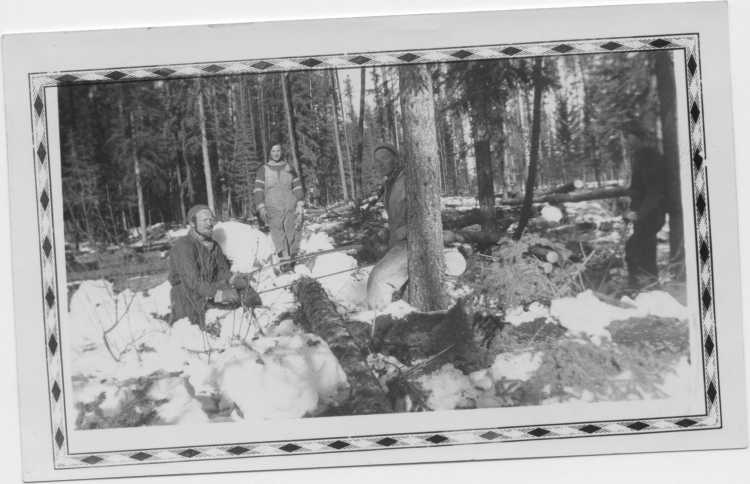

COs sawing logs in the bush |

Page

1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page

4 | Page 5

| Back to Work Page |