Back to Support from Home Page

Canadians

in the 1930s were, in general, much less mobile than they are today.

Traveling was a luxury. Many people did not expect to leave their

province, never mind the country, during their lifetimes. Mennonites

had even less experience with traveling for work or pleasure. They

were usually content to stay in their own communities.

For

many young Mennonite men, living in alternative service work camps

was the first time they have been away from home. Telephone service

was often unavailable. If it was, it could be unreliable. Writing

letters was the main means of communication for COs and their friends

and family.

Mail

call was the highlight of the day for many. A camp official or CO

would collect all the mail and the men would gather around while

he read out the names and handed out the mail. “What a joy for those

who had a letter,” Henry Sawatzky remembers. He, himself, was an

avid writer. During his four-month term at Clear Lake, Manitoba,

he wrote 69 letters. This, he says, was “a good indication that

we were not used to being away from home. Postage on a letter was

$.03 at that time, and our pay was $.50 a day.” [ ASM ,

7-11]

Clear

Lake, in Riding Mountain National Park, was relatively accessible.

Mail arrived daily. In Montreal River, it was a different story.

“During the winter,” Noah Bearinger says, “we only received mail

once a week or rarely twice, but when the roads dried up in spring,

we had better service.”

The

first video is of the mail call at Montreal River. The second video

shows a CO writing a letter home to his girlfriend.

The

camp at Montreal River was one of the first to host COs. In the

six months after it opened in June 1941, COs there received 2,604

letters and 349 parcels. The Northern Beacon, a newspaper

for COs, reported the total of 2,955 with amazement. They also noted

that the number would have been much higher if they had included

the Christmas season.

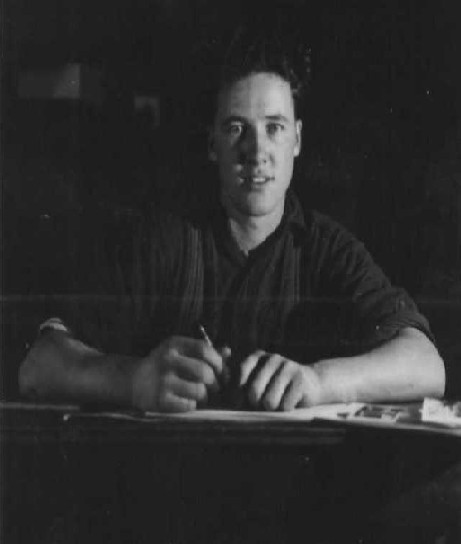

|

| A CO in BC writing a letter |

Bearinger

had a girlfriend back home in southern Ontario. When letters came,

he would eagerly look through his letters to see if she had written.

“Other letters that we had received were less important,” he says.

If she had sent him a letter, he sat on his bunk “reading the letters

real slow to let the meaning of each word soak in like the warm

rays of an April sun.” Only after reading this letter would he read

letters from his friends and family. At times these letters were

a bit disappointing, especially considering the high expectations

the COs had. The letters all seemed to say the same things: “Hope

you are all healthy and hope you can all be home for seeding time,”

or “The ministers remembered the boys in camp in their prayers Sunday,”

or “I hope one and all can stay steadfast in their faith, whatever

your lot.” [ASM, 105] These fine thoughts were small consolation

to COs who were dreadfully homesick.

|

| Fred Cressman sitting on his bunk writing a letter |

At

other times, the mail was much more interesting. The care packages

sent from home could be especially exciting. The COs never knew

what to expect. Sometimes they got knitted socks, sometimes some

baked goods. One CO even received a fully cooked pork roast!

Just

as Canadian families missed their sons and daughters who were serving

in the military, so the families of COs missed their sons and daughters.

It was hard for parents when their children left home, especially

under such dreadful circumstances as war.

David Jantzi was sent to an alternative service camp for the duration

of the war. He left a young family behind not knowing how

long he would be away.

David Jantzi was sent to an alternative service camp for the duration

of the war. He left a young family behind not knowing how

long he would be away.

Read

some examples of CO mail.

Back to Support from Home Page

|